Unusual Objects No. 12

“Anderlecht butter”: between myth and reality

During the reorganisation of the beguinage, Erasmus House is highlighting an unusual object from the vast historical, archaeological, folk art and religious art collections of the municipal museums each month. This month our museum is displaying butter moulds, Anderlecht having been renowned for its butter.

1. Circular wooden butter mould depicting a bull lying down

Belgium

Wood

1900-1950

Diam.: 7.5 cm

Inv. BEG 5600

2. Butter mould

Circular wooden butter mould depicting a fish

Belgium

Wood

1900-1950

Diam.: 7.2 cm

Inv. BEG 03800

The first 19th century tourist guide books painted a bucolic picture of Anderlecht as a territory covered with lush green pastures dotted with peacefully grazing cows. The milk that was collected was used to make “Anderlecht butter”. The quality and refined taste of this butter made it one of the most highly appreciated foods in Brussels. The Erasmus House and Beguinage Museums will now take you on a journey through this local past, with moulds used to make this dairy product as its stepping stones.

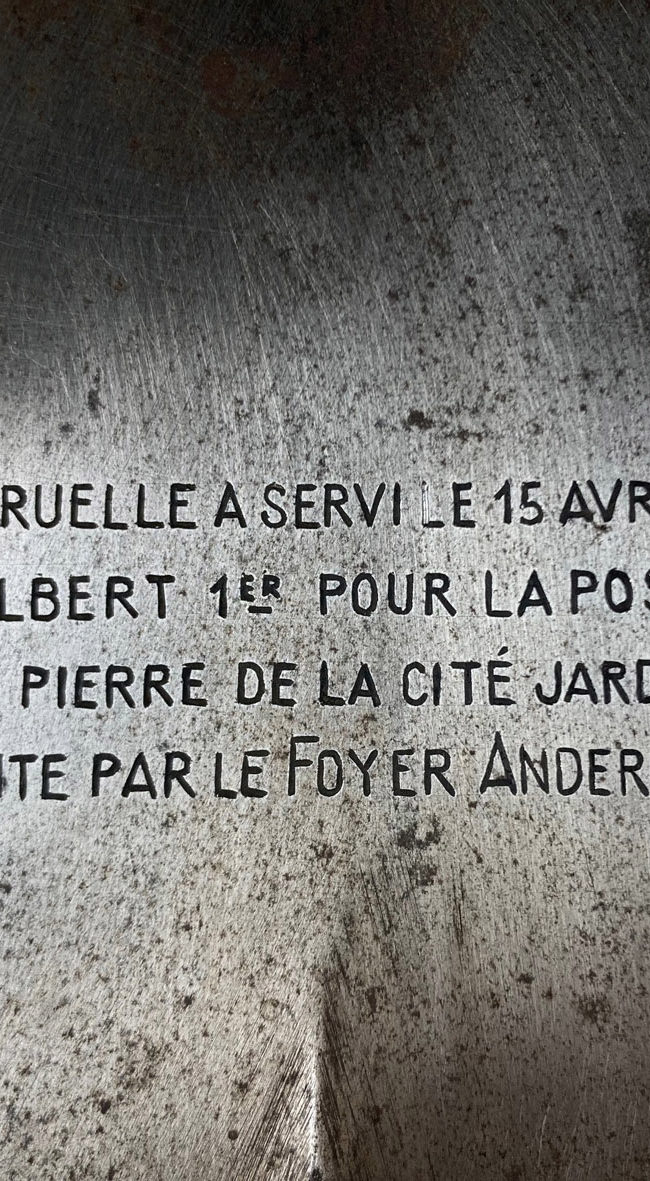

Legend

The story of its success started when Saint Guy (ca. 950-1012), sexton of Our Lady of Laeken Church and Patron Saint of Anderlecht, blessed the butter of this region, explaining its excellent quality and the renown that it enjoyed thereafter. Several centuries later, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) asked a dairy maid named Alena, who came from Anderlecht , for something to eat during a summer walk in the village. She offered him him some buttered bread with milk to drink, both locally produced dairy products. At the end of the meal, the august guest, won over by these foods, promoted the young woman farmer, giving her the title of Purveyor to the Court. From that moment on, all the dairy women of the municipality of Anderlecht claimed to be Alena’s descendents and were allowed to stamp their products with the imperial crown.

The reputation of Anderlecht butter is attested by historical documents. So, a report on the Dyle Department, of which Brussels was the departmental seat, said it was the most sought after and best butter in the region. Whilst butter was a major dietary mainstay in the 18th century, its consumption dropped significantly thereafter. Some analysts attribute this dietary change to shrinking herds as the human population grew.

The production of Anderlecht butter

Whilst we still hear echoes of the fame of this food today, in contrast very little information about how it was made has come down to us. The making of butter, which has been known since Antiquity, has changed little over the centuries. First of all, the milk is separated from the cream, which is set aside to mature a few days before being transferred to a churn. The process of churning the cream separates the butter fat from the whey. The resulting lumpy mass is creamed until smooth and then pressed into a mould. The moulds shown here were used not only to estimate the weight of the resulting block of butter, but also to decorate it or to stamp it with the diary’s emblem. Most of the time they presented variations of agricultural themes and the museum’s pieces are not exceptions to the rule. They thus depict a bull lying down, a flower, and even a fish. Judging by the quality of the designs represented, these moulds were made in the first half of the 20th century by bushel makers or boisseliers in French. These were craftsmen who were specialised in curving wood to make measures for grain and other foods, with the French name derived from the old unit of measurement, boisseau (bushel). Although due to the dictatorship of modern slimming diets butter is no longer so high and mighty, it was people’s main source of fat intake for centuries, as attested by the butter moulds and stamps in our museums, including specimens similar to the ones in our collection that can be admired in the Walloon Life Museum in Liège. The story of Anderlecht butter is far from just legend. It is incarnated in these few artefacts that have come down to us from the past as witnesses of bygone practices.

More info

Practical info

Research and text

Meggy Chaidron

Acknowledgements

Zahava Seewald, Céline Bultreys, Marcel Jacobs